Alabama Indigenous Peoples in Revolutionary Times

Indigenous Peoples in Alabama

The Cherokee

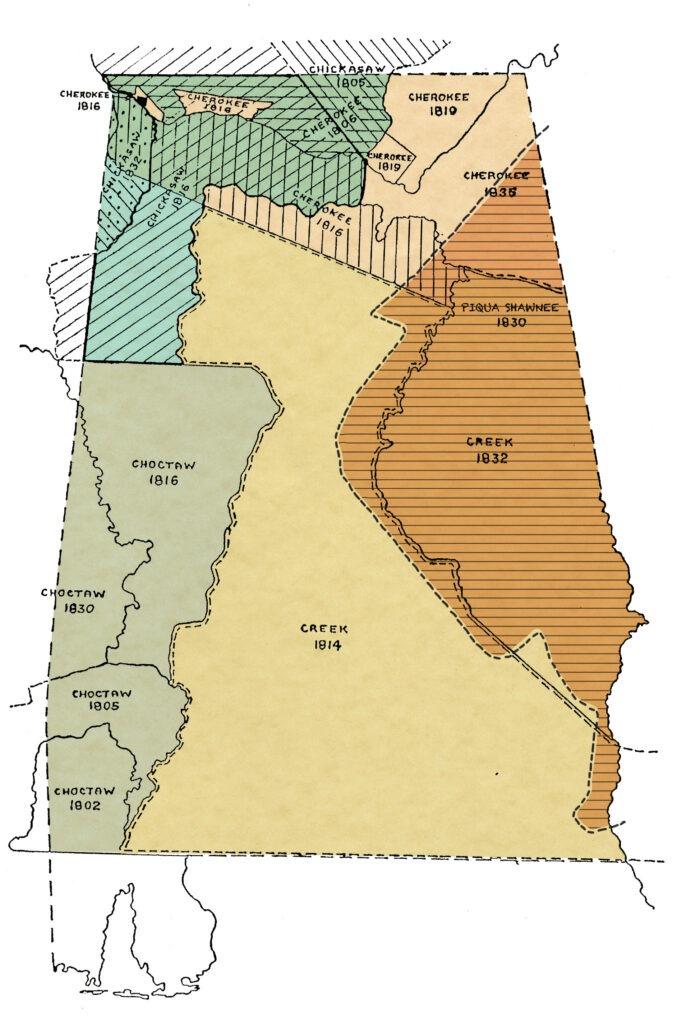

Alabama became part of the Cherokee homeland only in the last quarter of the eighteenth century. Nevertheless, this population of Native Americans significantly contributed to the shaping of the state’s history.

Their presence in Alabama resulted from a declaration of war against encroaching white settlers during the American Revolution era. A few decades later, the Cherokees served as valuable allies of the United States during the Creek War of 1813-14. Although the Cherokees fought alongside the United States under Gen. Andrew Jackson, he later campaigned for their removal from the Southeast. Land hunger among whites led to the Indian Removal Act of 1830, which in 1838 resulted in the forced removal of the Cherokees to Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River.

Cherokee settlements had historically occupied the fertile river valleys of the southern Appalachian Mountains in present-day northwest South Carolina, western North Carolina, east Tennessee, and north Georgia. Mountains separated these towns into three distinct regions: the Lower Towns, the Middle and Valley Towns, and the Upper or Overhill Towns. Their traditional hunting territory encompassed parts of Tennessee, Kentucky, and Virginia. The effects of war and subsequent land cessions forced the Lower Towns to resettle north and westward during the era of the American Revolution. And by 1782, the Cherokees had begun to establish settlements in what is now northeast Alabama in present-day Madison, Jackson, Marshall, DeKalb, Cherokee and Etowah counties and even as far west as Colbert county.

Three Cherokee Chiefs, 1762

During the war, the Chickamauga, a pro-British faction of Cherokees, split from the Upper Towns on the Little Tennessee and Hiwassee Rivers in east Tennessee. Led by war chief Dragging Canoe and supported by British agents and sympathetic traders, the Chickamauga left to establish towns farther down the Tennessee River. Two of these, Long Island Town and Crow Town, were located on the river near present-day Bridgeport, Jackson County. Nickajack and Running Water were just upriver near South Pittsburg, Tennessee, not far from Lookout Mountain Town in the extreme northwest corner of Georgia. From these Five Lower Towns, the Chickamauga launched raids on American backcountry settlements from middle Tennessee to southwestern Virginia. In 1792, Dragging Canoe died and his nephew John Watts became the leading war chief. Two years later, Tennessee militia leader James Ore launched a military expedition to punish the Chickamauga for their raids. The assault was devastating and resulted in the Cherokees suing for peace with the United States.

By 1800 many Cherokees lived on dispersed farmsteads in northeast Alabama. They established communities at Turkey Town, Wills Town, Sauta, Brooms Town, and Creek Path at Gunter’s Landing, all of which provided leadership within the Cherokee Nation. Several of the towns served as sites of tribal councils. With the encouragement of the U.S. government, Christian missionaries established schools at Creek Path (1820) and Wills Town (1823). And as part of the U.S. plan of civilization (formalized with regard to the Cherokees by the 1791 Treaty of Holston), the federally appointed agent to the Cherokees provided looms, spinning wheels, and plows to encourage Cherokee women to take up domestic arts and Cherokee men to give up hunting for farming and herding. In 1806, as hunting declined among the Cherokees, the U.S. sought and won a land cession, significantly shrinking Cherokee land in Alabama by 1,602 square miles.

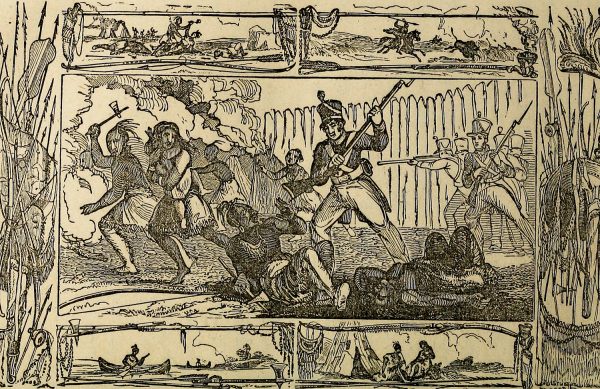

Battle of Tallushatchee

When war broke out in 1813, the Cherokees refused to join the faction of Creeks known as the Red Sticks, who were hostile to the United States. Instead, they fought alongside the Tennessee and U.S. troops under Andrew Jackson. Together they raided Creek villages along the Black Warrior River and fought in the November 1813 Battles of Tallushatchee and Talladega, from which they emerged victorious. Cherokee warriors played a major role in the attack on the Creeks of the Hillabee towns, who were members of the Red Stick faction. Following orders issued by Gen. John Cocke, the attacking party was unaware that the Hillabee had recently surrendered to Jackson. This one-sided assault became known as the Hillabee Massacre.

After American setbacks at the Battles of Emuckfaw and Enotachopco Creek in January 1814, the main Cherokee force joined Jackson for his assault on a large body of Red Sticks at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend on the Tallapoosa River in east-central Alabama on March 27, 1814. Here the Cherokees crossed the river and created a rear diversion. This unplanned but successful action allowed Jackson’s troops to make a frontal assault over a formidable defensive log barricade and resulted in the killing of approximately 800 Red Sticks. This outcome decisively ended the war.

Although allied with the United States, the Cherokees suffered from the war as well. Some East Tennessee troops traveling through Cherokee territory destroyed property and terrorized families. Most of the damage occurred in the Sequatchie Valley and Wills Valley areas of present-day Alabama. It was not until 1817 that the U.S. government settled Cherokee claims amounting to $25,500.

After the war, the U.S. government negotiated the Treaties of 1817 and 1819, which called for more Cherokee land cessions. Up to this time, the Chickasaw-Cherokee and the Cherokee-Creek boundary lines were not officially established. The United States paid the Chickasaws and the Cherokees, both allies during the late war, for lands north and south of the Tennessee River, as well as west of the Coosa River. Some Cherokees refused to leave their farms on ceded land and took advantage of a clause to claim private reserves. But most left their farms to relocate onto the shrinking tribal lands. Several hundred chose to journey across the Mississippi River to join the Old Settler Cherokees, a group that had emigrated prior to 1820.

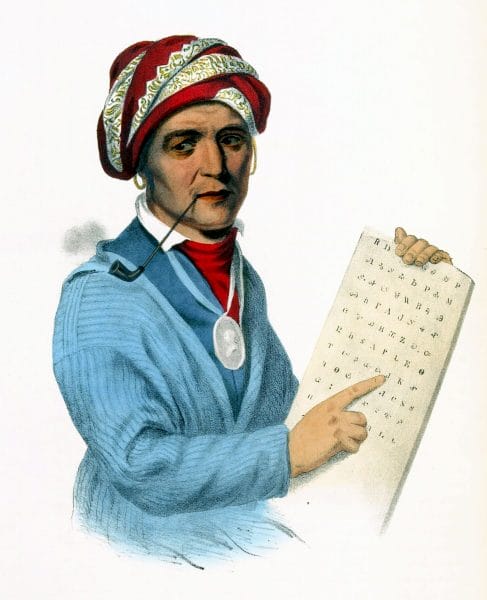

Sequoyah

Another seminal event occurred after the war. Sequoyah, or George Guess, a veteran of the Creek War, lived in Wills Town (in present-day northeastern Alabama), where he developed a syllabary for writing the Cherokee language. In 1821, the Cherokee Council at Sauta approved its distribution to the people. The dissemination of Sequoyah’s syllabary transformed the Cherokee Nation into a literate populace within a few months.

Other prominent Cherokees lived in northeast Alabama. Cherokee siblings David and Catherine Brown became Christian converts at Wills Town Mission. David became one of the first Cherokee-speaking ministers, and Catherine became a mission schoolteacher. Double Head, a notorious Chickamauga warrior and chief, was executed in 1807 for selling Cherokee land for private gain. His brother-in-law Tahlonteskee emigrated west shortly thereafter and became a leader among the Old Settler Cherokees. Path Killer of Turkey Town served as principal chief during the Creek War of 1813-14. George and John Lowry served as military officers in the war, and George later became second chief.

Source: The Encyclopedia of Alabama

Further Reading

- Bunn, Mike. Fourteenth Colony: The Forgotten Story of the Gulf South During America’s Revolutionary Era. Montgomery: NewSouth Books, 2020.

McLoughlin, William G. Cherokee Renascence in the New Republic. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1986.

Mooney, James. History, Myths, and Sacred Formulas of the Cherokees. Asheville, N.C.: Historical Images, 1992. - Levasseur, Auguste. Lafayette in America in 1824 and 1825; or Journal of a Voyage to the United States. Translated by John D. Godman. New York: Research Reprints, 1970.

- McWilliams, Tennant S. “The Marquis and the Myth: Lafayette’s Visit to Alabama, 1825.” Alabama Review 22 (April 1969): 135-146.

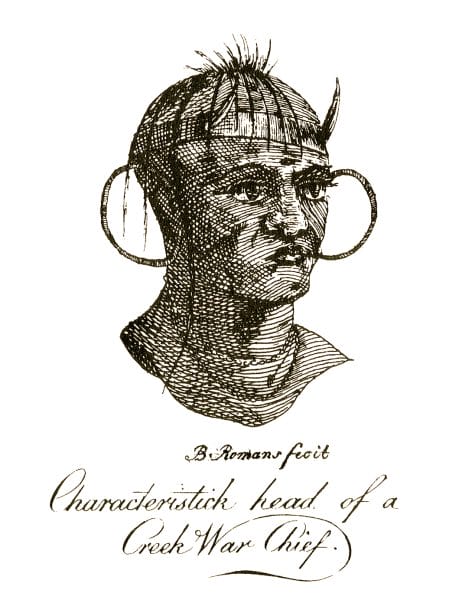

The Creek

A confederacy of a number of cultural groups, the Creeks played a pivotal role in the early colonial and Revolutionary-era history of North America.

In 1775, author and trader James Adair described the Creek Indians as “more powerful than any nation” in the American South. Despite the fact that they were able political and economic partners of the colonial and early U.S. government, the Creeks suffered the same fate as their fellow Southeastern tribes, and many of them were forced from their lands in the 1830s. However, Creek culture is kept alive in Alabama among the Poarch Band of Creek Indians, based in Escambia County.

William McIntosh

The Creek Indians, along with other Southeastern tribes such as the Choctaws and Cherokees, are descended from the peoples of the Mississippian period (ca. AD 800-1500), known for its giant earthen mounds and complex, hierarchical social structure. In the sixteenth century, the arrival of Europeans brought epidemics and widespread warfare and violence to the Southeast, resulting in the scattering of the region’s indigenous peoples. Beginning in the seventeenth century, these diverse populations joined together and established settlements along the central Chattahoochee River, the lower Tallapoosa River, and the central Coosa River in what is now east-central Alabama. For the next two centuries, these areas served as the heart of what came to be called Creek country, and these new towns (talwa in the Muskogean language of the Creeks)—devoid of the earthen platform mounds that typified Mississippian villages—became the centers of Creek political and ceremonial life and defined the political identity of each Creek individual.

As a political unit, the Creek Nation grew gradually during the century and a half prior to their removal from Alabama in the 1830s. From as few as perhaps 9,000 persons in the 1680s, the Creek population increased to about 20,000 by the time of the American Revolution and exceeded 21,000 at the time of removal. Muskogee- and Hitchiti-speaking peoples from the main Creek towns made up the major portion of the population. But the Creek nation was multiethnic and included Indian peoples from Spanish missions in Georgia and Florida as well as Yuchi, Shawnee, Chickasaw, and Natchez refugees, who fled to Creek country to escape intertribal warfare and conflicts with French and Spanish colonists.

Creek Identity

Though the numbers fluctuated over time, the Creek nation was generally comprised of between 30 and 60 towns (talwa), with each group primarily identifying itself with the major town in its region. Thus national unity was often hard to come by in Creek country, given the independence of each town and the multiethnic composition of the nation. In fact, the name “Creek” was a term English traders first used as a convenient way to label the people of various Creek towns. The Creeks themselves tended to view their nation as a confederacy consisting of three distinct provincial groups: the Ochese or Coweta of the Chattahoochee River basin, the Tallapoosa of the lower Tallapoosa River, and the Abeika of the upper Tallapoosa and Coosa rivers. The British and Americans, however, tended to refer to the first group as the “Lower Creeks” and the latter two groups together as the “Upper Creeks.”

The Creek people applied kinship terminology to designate each town’s relationship to others, based upon the perceived age of a town or size of its population. The Creeks regarded older towns, for instance, as “grandmother” towns, whereas newer towns often carried the designation of “daughter” or “grandchild” towns. The Creeks also divided their nation into “war” and “peace” towns, represented by the colors red for war and white for peace. In diplomacy and warfare, the groups represented by each town could act as independent units, as each was comprised of a dual hierarchy of civil and military offices. The Creek peoples recognized some groups and their towns as particularly influential in national affairs. Creek oral tradition describes the Coweta, Cusseta, Tuckabatchee, and Abeika as the four “foundation” groups of the nation. The Coweta and Cusseta, according to Creek histories, were closely related and exercised great influence among the Creeks of the Chattahoochee River. Leaders of towns among the Tuckabatchee, Okchai, Okfuskee, Talassee, and Abeika tended to dominate political affairs among the Creeks of east-central Alabama.

The Creeks are culturally and linguistically related to other southeastern Indian tribes, particularly Muskogean-speaking peoples such as the Choctaw and Chickasaw. And like their Indian neighbors, the Creeks were horticulturalists who grew corn and several other crops, supplemented by seasonal hunting for white-tailed deer and other game animals.

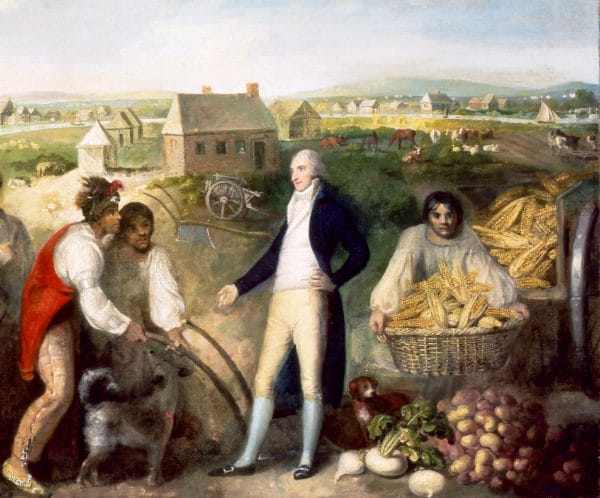

Benjamin Hawkins and the Creek Indians

Creek contact with European colonists was intermittent at first and largely occurred through trade and diplomacy with Spanish Florida. Their involvement with colonial powers became more pronounced by the middle of the 1680s, when traders from South Carolina began venturing directly to Creek villages. A brisk trade ensued, and colonial traders exchanged cloth, guns, and steel tools for deerskins and, notably, Indian slaves taken in warfare from other tribes. In 1690, in order to facilitate trade with the South Carolinians, the Chattahoochee towns and allies from among the Tallapoosas and elsewhere moved and relocated their towns on the Ocmulgee and Oconee Rivers in central Georgia. At one such town—Ocmulgee—English traders built a permanent trading post that has been the subject of archaeological investigation. Its remains are contained within the Ocmulgee National Monument in Macon, Georgia.

The years that the Creeks spent in central Georgia (ca. 1690–1715) proved to be pivotal ones. Because of their ties to South Carolina traders, they became deeply immersed in the trade in deerskins and Indian slaves, as well as the conflicts with Britain’s imperial rivals, Spain and France. Creek war parties played an important role in destroying Spanish Indian missions along the Georgia coast and in the Florida mission provinces among the Timucuas and Apalachees, whom the Creeks often enslaved or sold as slaves to the South Carolinians. Having brought Spanish Florida to near ruin by 1706, the Creeks began seeking slaves in such far-off places as the Florida Keys and the Choctaw settlements of Mississippi. English officials compelled Creek war parties to assist in their wars against Spanish and French outposts (Queen Anne’s War, 1702–13) and against the rebellious Tuscarora tribe of North Carolina (Tuscarora War, 1711–12). By 1715, the Creeks and other Indian nations found that their formerly beneficial relationship with South Carolina had ensnared them in a cycle of debt and warfare that compromised their economic well-being, if not their cultural and territorial integrity.

The Yamasee War of 1715 ushered in a new diplomatic era in Creek history. On Good Friday (April 15, 1715), the Yamasees, Creeks, and other allies launched a war against South Carolina, while at the same time seeking new alliances with the Spanish and French. By the end of the war the Creeks had settled upon a strategy by which they pledged to remain neutral in times of war between the three European powers. Established at a meeting in the Lower Creek town of Coweta in March 1718, and devised by that town’s chief, known to the English as the “Emperor” Brim, the policy of neutrality increased their political leverage by enabling them to defend their ancestral territory by “playing off” one European power against another. Creek leaders, for example, welcomed the French and allowed them to build Fort Toulouse at a location near Wetumpka, Elmore County, while at the same time they maintained their economic relationship to traders in South Carolina and, later, Georgia. Neutrality became the distinguishing characteristic of Creek diplomacy for the remainder of the colonial era. Their neutral status, though precarious at times, enabled the Creeks to trade with Europeans with little disruption and may account for Creek population growth before the American Revolution.

The revolution, which played an integral role in stimulating the westward movement of Anglo-American settlers in the decades that followed, brought about revolutionary developments for the Creeks as well. At that time, the most influential Creek leader was Alexander McGillivray, the son of a Scottish trader and Creek mother. McGillivray was instrumental in encouraging cooperation among the various Creek towns and courting the assistance of the Spanish in Florida to help the Creeks defend their land against the Americans. But U.S. government pressure proved too much to bear, and the Creeks ceded their remaining Georgia lands in treaties negotiated in 1790, 1802, and 1805. The Creek economy likewise began to bear stronger resemblance to the plantation economies of the Lower South, as many Creeks (often the bi-cultural sons of Scottish fathers and Creek mothers) began introducing cotton and plantation slavery into the region.

In an effort to assimilate southeastern Indians, the U.S. government enacted its plan of civilization, as the effort became known, in 1796 and placed Indian agent Benjamin Hawkins in charge. Under the plan, the Creeks and other southeastern tribes were to receive instruction in commercial farming, animal husbandry, cloth spinning, and the principles of Christianity. Hawkins also attempted to centralize the Creek government by creating a police force, a Creek National Council and by encouraging the creation of written laws.

Many Creeks accepted, if not embraced, the new order of things. Creek leaders such as William McIntosh of the Coweta and Big Warrior of the Tuckabatchee benefited from the new economy and became close allies with Hawkins and other U.S. agents. Many opened taverns and stage stops along the newly constructed Federal Road, which connected Fort Mitchell, in present-day Russell County, with Mobile. Creek traditionalists, in contrast, became increasingly defensive of their sovereignty and culture. Their concerns reached new heights after white settlers began pouring into Alabama Territory on the Federal Road. In 1813, a group of warriors belonging to this traditionalist group, inspired by local “prophets” such as Josiah Francis (Creek name, Hilis Hadjo) and the pan-Indian, nativist movement founded by Shawnee warrior Tecumseh (who himself visited the Creeks in 1811), began fighting back. The Creek War, also known as the Red Stick Revolt after the red war clubs carried by the Creek fighters, was partly a war against the U.S. government and partly an internal war between rival Creek factions led by Francis and Big Warrior. After scoring early victories at places such as Ft. Mims, the Red Stick Creeks, led by Menawa, were ultimately defeated by U.S. forces, led by Gen. Andrew Jackson, and their Creek and Cherokee allies at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend (1814). In the subsequent Treaty of Fort Jackson (1814) and Treaty of Indian Springs (1825), the Creeks ceded all of their remaining lands in Georgia, causing the nation to relocate entirely into Alabama. Only a small faction of Creek leaders, led by William McIntosh, signed the Indian Springs treaty, and many Creeks thus viewed it as fraudulent. Under Creek law, McIntosh’s action was punishable by death, and the Creek National Council shortly thereafter executed McIntosh and three others who had signed the treaty.

Source: The Encyclopedia of Alabama

Further Reading

Saunt, Claudio. A New Order of Things: Property, Power, and the Transformation of the Creek Indians, 1733–1816. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Braund, Kathryn E. Holland. Deerskins and Duffels: The Creek Indian Trade with Anglo-America, 1685–1815. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1993.

Bunn, Mike. Fourteenth Colony: The Forgotten Story of the Gulf South During America’s Revolutionary Era. Montgomery: NewSouth Books, 2020.

Green, Michael D. The Politics of Indian Removal: Creek Government and Society in Crisis. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1982.

Hahn, Steven C. The Invention of the Creek Nation, 1670–1763. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004.

Martin, Joel. Sacred Revolt: The Muscogees’ Struggle for a New World. Boston: Beacon Press, 1991.

Piker, Josh. Okfuskee: A Creek Indian Town in Colonial America. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2004.

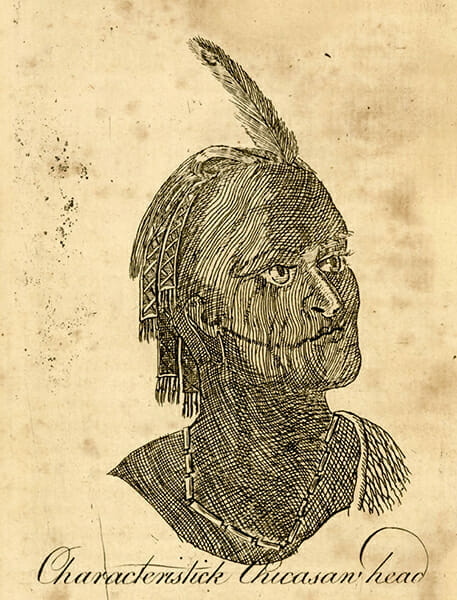

The Chickasaw

Although the Chickasaw Nation was primarily located in present-day Mississippi, their actions during the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth century had a great impact on early Alabama history. The tribe successfully negotiated complicated trade and military alliances with the French, the British, and the U.S. government following the American Revolution.

Despite their efforts to adapt to increasing numbers of white settlers after the war, they were eventually forced to cede their territory, along with the Creeks, Choctaws, and Cherokees, and remove to present-day Oklahoma. Today, the members of the Chickasaw Nation reside largely in 13 counties in south-central Oklahoma.

Chickasaw Lifeways

The Chickasaw Indians traditionally lived in what is now Northwestern Alabama, Northern Mississippi, and Southwestern Tennessee. Their population fluctuated between 2,000 and 5,000 throughout the eighteenth century, and their villages were concentrated in the area of present-day Tupelo, Mississippi. Though smaller in numbers than other neighboring Indian tribes, such as the Creeks and the Choctaws, the Chickasaws’ impact on Alabama and the Southeast was significant.

The Chickasaws were culturally related to their southern neighbors the Choctaws. They spoke a dialect of the Western Muskogean language family shared by many of the Southeast’s Native American societies. Like all southeastern Indians, the Chickasaws traced lineage according to matrilineal rules of kinship, which meant an individual was only related to his or her mother’s family and that the primary father figure in a child’s life was likely a maternal uncle rather than the biological father. Chickasaw women controlled their own resources and land, where they raised the crops that all Chickasaws depended upon. By the eighteenth century, the Chickasaws lived in approximately 10 towns in northeastern Mississippi and in other locations among the Upper Creeks from 1722 to 1740 and farther east along the Savannah River from 1723 until around 1776. Following the Natchez War against the French in 1729, a contingent of Natchez people joined the Chickasaws as a separate village. But each village maintained its own set of war chiefs, civil chiefs, and other officers that may have been determined by clan membership, with 15 distinct clans. The Chickasaw villages fell into one of two basic groupings, or moieties, called the Spanish clan or Panther clan, and each division maintained its own ritualistic leaders and governance.

Contact with European Explorers

The Chickasaws’ first interactions with Europeans occurred during the winter of 1540-41, when they repeatedly attacked Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto and his expedition until they moved west across the Mississippi River, culminating in a major engagement on March 4, 1541, when the Chickasaws nearly overran Soto’s forces and killed 12 Spaniards, 56 horses, and hundreds of pigs. Those brief encounters were the only significant contact that the Chickasaws had with Europeans until the founding of Charles Town (Charleston) in Carolina by the English in 1670. British traders sought to trade guns, metal goods, manufactured cloth, and other items with the Chickasaws for deerskins and Indian captives, who were then sold as slaves to sugar plantations in the Caribbean. The Chickasaws became prominent slave traders in the early colonial South at the expense of their Indian neighbors, enhancing their wealth and political position as middlemen between the British and other tribes. French explorers and traders, who had established a presence on the Gulf Coast, chose to trade with their principal Indian allies, the Choctaws, to the dismay of the Chickasaws. Partly for this reason, around 200 Chickasaws, led by chief Squirrel King, relocated farther east to the Savannah River in the 1720s to be nearer the English and their trade goods.

Conflict with the Choctaws and the French

The Chickasaws’ close relations with the English led the French, under Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, into conflict with the tribe that lasted for several decades and had a ruinous effect. The French colonial government could not afford to trade with all Indians in the lower Mississippi Valley, and they chose to cut their losses by cultivating the large Choctaw population as allies to the exclusion of some smaller groups such as the Chickasaws. Beginning in 1720, the Chickasaws sparked a conflict with the French and their Choctaw allies after Chickasaw warriors killed a French fur trader whom they and the English accused of being a spy. In retaliation, the French provided more guns and ammunition to the Choctaws and encouraged them to attack the Chickasaws. All of the Choctaw assaults were repelled by the Chickasaw, who then went on the offensive and effectively cut off all French shipping on the Mississippi River. The Chickasaws and Choctaws established peace in 1724 and the French agreed to abide by the new agreement in 1725.

The peace agreement was short-lived, however. In November 1729, the Natchez Indians rebelled against the French settlers in their midst, killing more than 200 of them. When the French retaliated in force, they killed many Natchez and took still more as prisoners. Natchez survivors were forced to abandon their home territory, and many of them sought refuge among the Chickasaws sometime around 1730 or 1731 in what is now Lee County, Mississippi, further angering the French. In 1736, the French and Choctaws launched a coordinated attack from the north and south against Chickasaw villages in northeast Mississippi that failed miserably, despite a nearly three-to-one advantage over the defenders. In 1739, the French mounted a new effort against the Chickasaws that also failed, and the two parties signed a truce in 1740. The Chickasaws again established peace with the Choctaws during the French and Indian War, ending decades of conflict, and Britain’s defeat of the French in 1763 removed them as a threat. The Chickasaws had survived France’s attempt to destroy them, but their population had dropped dramatically to about 3,000 during this period as a result of the constant warfare.

The American Revolution

With their ally and long-time trading partner Great Britain in control of much of the eastern territory of the Gulf of Mexico and east of the Mississippi River after 1763, the Chickasaws experienced few threats. In 1765, tribal leaders representing the Chickasaws and Choctaws met with British negotiator and former French officer Henrí Montault de Monbéraut de Saint-Çivier in Mobile under the auspices of George Johnstone, governor of British West Florida, and signed the Treaty with the Choctaws and Chickasaws. That agreeable situation ended, however, when the American Revolution erupted in 1776. The Chickasaws tried to remain neutral, but they felt most committed to the British cause because of the long history between the two nations. The only battle between the Chickasaws and Americans during the war occurred in 1780, when some Chickasaws briefly attacked George Rogers Clark’s Fort Jefferson in western Kentucky. After the war the Chickasaws quickly established relations with the United States and with Spain, which controlled the entire Gulf Coast from Florida to Texas.

During the 1780s and 1790s, the Chickasaws played the United States and Spain off of one another, trading with both countries while refusing to be dominated by either. Skillful diplomacy had always been important for the Chickasaws in retaining their sovereignty, but in 1795, under the Treaty of San Lorenzo (also called Pinckney’s Treaty), Spain ceded all claims to land above the 31st parallel, thus placing all Chickasaw lands within the boundaries of the United States. The Mississippi Territory (including present-day Alabama) was formed three years later in 1798, and Americans flooded into lands along the Mississippi River and then along the Natchez Trace, which crossed through the middle of Chickasaw lands. By 1809 there were an estimated 5,000 American squatters living on Chickasaw land.

Source: The Encyclopedia of Alabama

Further Reading

Swanton, John R. Chickasaw Society and Religion. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2006.

Adair, James. The History of the American Indians. Kathryn Holland Braund, ed. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2005.

Atkinson, James R. Splendid Land, Splendid People: The Chickasaw Indians to Removal. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2004.

Bunn, Mike. Fourteenth Colony: The Forgotten Story of the Gulf South During America’s Revolutionary Era. Montgomery: NewSouth Books, 2020.

Fitzgerald, David G. Chickasaw: Unconquered and Unconquerable. Ada, Okla.: Chickasaw Press, 2006.

Gibson, Arrell M. The Chickasaws. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1971.

Hoyt, Anne Kelley. Bibliography of the Chickasaw. Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 1987.

Scrivner, Fulsom Charles. The Early Chickasaws: Profile of Courage. New York: Vantage Press, 2005.

The Choctaw

The Choctaw Indians once lay claim to millions of acres of land and established some 50 towns in present-day Mississippi and western Alabama. With a population of at least 15,000 by the turn of the nineteenth century, the Choctaws were one of the largest Indian groups in the South and played a significant role in shaping the politics, economics, and armed conflicts in the region.

Thousands of Choctaws remained in the Southeast even after removal and are known today as the federally recognized Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians and the state-recognized MOWA Band of Choctaw Indians (so named for their location in Mobile and Washington County) Choctaws of Alabama. Other Choctaw people live in the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, in Choctaw communities in Texas and Tennessee, and as families or individuals throughout the United States.

The peoples who became known as the Choctaws (they call themselves Chahtas) originally lived as separate societies throughout east-central Mississippi and west-central Alabama and all spoke dialects of the Muskogean language. From at least the eighteenth century, there existed among the Choctaws a confederacy of three principal geographic and political groups: the western, eastern, and Six Towns (or southern). The villages of the western division were scattered around the upper Pearl River watershed in east-central Mississippi; the eastern division towns were located around the upper Chickasawhay River and lower Tombigbee River watersheds along the lower Alabama-Mississippi border; and the Six Towns were distributed along the upper Leaf River and mid-Chickasawhay River watersheds in southeast Mississippi.

Predecessors

The members of the eastern division may have descended from the Mississippian peoples of the Moundville chiefdom of west-central Alabama around present-day Tuscaloosa. The western peoples lived historically among the headwaters of the Upper Pearl River, and the Six Towns descended from peoples who lived in the southern and southwest regions of Mississippi. These independent societies likely first moved near each other sometime after Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto’s expedition through the southeastern United States in the early 1540s and before 1699, when the French arrived on the Gulf Coast. Each village within the division maintained its own chiefs and other leaders well into the nineteenth century. The eastern Choctaws also maintained a close ethnic and cultural relationship with the Alabama Indians, who lived at the junction of the Coosa and Tallapoosa Rivers. One prominent eastern-division Choctaw chief of the eighteenth century, for example, was named Alibamon Mingo (meaning Alabama chief) and may have had kinship ties to the Alabamas.

In the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, various Creek villages and the Chickasaws repeatedly attacked the Choctaws to seize captives for sale as slaves to British planters in South Carolina. Indian societies throughout the Southeast traditionally warred against one another for a variety of reasons before and after Europeans arrived on the continent. The Creeks and Chickasaws used the firearms they acquired from trade with the British to capture as many as 2,000 Choctaws, who were then sold to work on sugar plantations in the British West Indies. When the French, under Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville, established the Louisiana colony at present-day Biloxi, Mississippi, in 1699, the Choctaws quickly established political and trade connections with them to acquire guns and fight off slave raiders. And Choctaws assisted French forces in attacking the Natchez Indians after the Natchez Revolt of 1729, and the Choctaws joined the French on several attacks against the Chickasaws.

Choctaw Civil War

Not all Choctaws wanted to trade only with France, however. Renowned Choctaw war leader Red Shoes, who hailed from the western division, opened trade with British fur traders based in South Carolina in the 1740s and ignited the Choctaw Civil War when he killed some French traders. Rivalries over trade with France and Britain caused the rift in Choctaw society, primarily between the western and eastern divisions, that lasted from 1747 to 1750. Eastern-division forces allied with France prevailed in the conflict and burned several western-division towns to the ground. Hundreds of Choctaws died during the war, which revealed deep divisions in the confederacy. After the conflict, Choctaw leaders worked to end inter-ethnic animosities and unite their peoples more closely.

After the civil war, some Choctaw towns and individuals continued to seek a trading relationship with Britain. Such independence was encouraged under the non-coercive leadership traditions of the Choctaws and other southeastern Indian groups. Because some Choctaw towns traded mostly with Britain while others traded primarily with France, the Choctaws, though not acting under any centralized national government, were nonetheless able to play the two European countries against each other, strengthening their hand in foreign diplomacy. Choctaws and their chiefs acquired European manufactured items, such as essential guns and wool cloth, by trading deerskins and other items to fur traders. The Choctaws who traded with Britain came out ahead when the French and Indian War broke out in the late 1750s, and French supply ships failed to arrive. Relations between eastern-division Choctaws and the French remained strong, however, until the French vacated the South after the conflict ended in 1763. All southeastern Indians thus opened or strengthened trade with Britain, and in 1765, tribal leaders representing the Choctaws and Chickasaws met with British negotiator and former French officer Henrí Montault de Monbéraut de Saint-Çivier in Mobile under the auspices of George Johnstone, governor of British West Florida, and signed the Treaty with the Choctaws and Chickasaws. These close relations remained intact after that war and through the subsequent American Revolutionary War. Most Choctaws who participated in the war defended British posts at Natchez, Mobile, and Pensacola against American and Spanish attacks, though some members of the Six Towns division supported Spanish military efforts against Britain.

Source: The Encyclopedia of Alabama

Further Reading

Young, Mary Elizabeth. Redskins, Ruffleshirts, and Rednecks: Indian Allotments in Alabama and Mississippi, 1830-1860. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1961.

Bunn, Mike. Fourteenth Colony: The Forgotten Story of the Gulf South During America’s Revolutionary Era. Montgomery: NewSouth Books, 2020.

Carson, James Taylor. Searching for the Bright Path: The Mississippi Choctaws from Prehistory to Removal. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1999.

DeRosier, Arthur H., Jr. The Removal of the Choctaw Indians. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1970.

Gaines, George Strother. The Reminiscences of George Strother Gaines: Pioneer and Statesman of Early Alabama and Mississippi, 1805-1843. Edited by James P. Pate. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1998.

Galloway, Patricia. Choctaw Genesis, 1500-1700. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995.

Kidwell, Clara Sue. Choctaws and Missionaries in Mississippi, 1818-1918. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1995.

Lincecum, Gideon. Pushmataha: A Choctaw Leader and His People. Introduction by Greg O’Brien. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2004.

Matte, Jacqueline Anderson. “Extinction by Reclassification: The MOWA Choctaws of South Alabama and Their Struggle for Federal Recognition.” Alabama Review 59 (July 2006): 163-204.

———. They Say the Wind is Red: The Alabama Choctaw—Lost in Their Own Land. Red Level, Ala.: Greenberry Publishing Company, 1999.

O’Brien, Greg. Choctaws in a Revolutionary Age, 1750-1830. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

The Piqua Shawnee

The Piqua Shawnee are one of five divisions of the Shawnee. They are known as the people of the south who rose from ashes. The Piqua Shawnee are the descendants of Ancestral Algonquians who have lived in Alabama since time immemorial. Like their neighbors, the Cherokee, Choctaw, and Muskogee (Creek), archaeologists refer to their ancestors as Paleoindians, Archaic, and Woodland peoples. Geographically, the range of these ancestral cultures covers the entire state of Alabama. Historically, they were well known for their production of salt, which became an essential trade item with the increased dependency on horticulture. The Piqua Shawnee processed salt from seawater, salt licks, and cave minerals.

The first European contact with the Piqua Shawnee likely occurred in 1540 when Admiral Maldonado, an officer of the Spanish conquistador Hernando de Soto, walked into the village of Ochuse (also spelled Achuse). This village site is located at Gulf Shores, in Baldwin County. The subsequent Spanish, French, and British settler colonial incursion resulted in chronic warfare and devastating epidemics. The Piqua Shawnee survived by adopting a mobile, semisedentary livelihood. This economic strategy included strengthening their long-time alliance with the Creek and the sharing of their towns and villages. It was customary for members of an entire Piqua Shawnee village to visit a Creek town for weeks or months at a time. In addition to feasting, commodities, customs, and stories were exchanged. Reciprocal tribal visits took place, which strengthened their political relationships. Intertribal commerce was a crucial aspect of the Piqua Shawnee culture and livelihood. The Piqua Shawnee relationship with the Creek greatly predates the European contact. As symbols of their ancient alliance, the Piqua Shawnee presented the Creek with seven metal pendants, which were displayed during the Green Corn ceremony.

Historic population estimates of the Piqua Shawnee are difficult if not impossible to calculate for four reasons: (1) the Piqua Shawnee were referred to as the Savannahs because of their distant towns along the Savannah River; (2) Europeans did not always distinguish between the Piqua Shawnee and the Creek when they were taking censuses of Creek towns and villages; (3) intermarriages with the Creek, Cherokee, Choctaw, Natchez, Yuchi, and settler colonists obfuscated their tribal identity; and (4), historic population estimates were affected when large groups of Piqua Shawnee traveled north to visit their distant kin the Ohio River valley.

Piqua Shawnee Identity

Figure 1. Traditional Piqua Shawnee warrior (courtesy of Ruth Morgan).

Figure 2. Historic Piqua Shawnee warrior (courtesy of Ruth Morgan).

Family is the primary social unit of the Piqua Shawnee. It is defined by a patrilineal kinship system in which an individual’s family membership is traced through the father’s clan. Each family clan is defined by a nonhuman totem in the Piqua Shawnee origin story. While we do not know exactly how many clans existed prior to European contact, there were 28 clans in 1825 (Bear, Big Fire, Buffalo, Cloud, Corn, Deer, Dirt, Elk, Fish, Fox, Hawk, House, Moon, Night, Otter, Panther, Rabbit, Raccoon, Skunk, Snake, Squirrel, Stone, Tree, Turkey, Turtle, Water, Wind, and Wolf).

Piqua Shawnee towns and villages were clan based. Family residence was patrilocal, a social system in which a married couple lived in the cabin or village of the husband’s parents. During the late eighteenth century, Piqua Shawnee towns were described as groups of wooden cabins built on a raised, pine tree covered, flat ground boarded by a river with agricultural fields on both sides of the river. Cabins were in the shape of oblong squares, approximately eight feet high, and covered with pine bark. Nuclear families were industrious as men worked together with the women. Towns and villages were clan based with a clan chief and a clan mother. Everyone in the town or village were members of a single clan. Tribal council was composed of a principal chief, a tribal mother a peace chief, a war chief, and clan representatives.

Linguistically, the Piqua Shawnee spoke an Algonquian group, Algic language, which was shared with 30 other tribes from the Atlantic Ocean to the Rocky Mountains. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the Piqua Shawnee raised horses and pigs, and corn was the primary agricultural crop. Domesticated foods were supplemented with the collection of wild plant foods (greens, berries, and masts) and wild game such as deer and turkey. Planting and hunting schedules were organized by lunar cycles. Grandmother Moon was an important part of their spirituality, and she was celebrated during the Spring Bread, Green Corn, and Fall Bread ceremonies. During these celebrations, there were standards of conduct for both men and women. There were also mutual obligations between people and the spirit world. Stories were told to young men and women to protect and ensure the cultural privacy of the tribe.

Contact with the Colonists

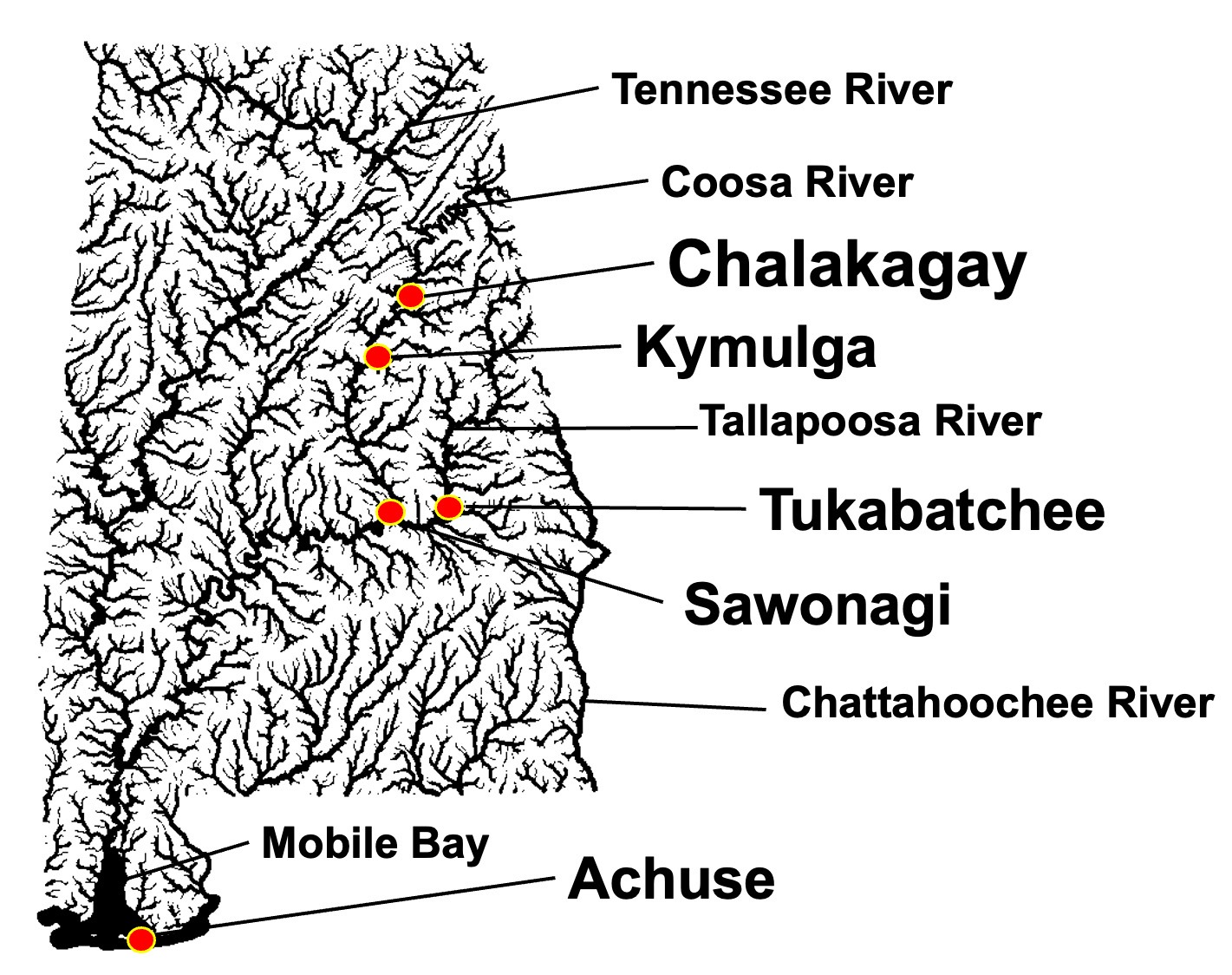

After initial contact with the Spanish in 1540, colonial traders regularly visited Piqua Shawnee settlements along the Chattahoochee River. By the late 1720s, Piqua Shawnee villages were located along the Coosa River. Sawonagi, a Piqua Shawnee town on the east side of the Tallapoosa River in Montgomery County, is best known as the home of Tekoomsē’s (Tecumseh) father (Puckeshinwau) and mother (Methoataaskee’). They grew up in separate Shawnee towns along the Tallapoosa River. Puckeshinwau was Kispoko Shawnee and Methoataaskee’ was Piqua Shawnee. She grew up in the town of Tukabatchee. In the late 1760s, Tecumseh’s parents moved to the Ohio River valley. While Tecumseh was born in the Kispoko Shawnee village of Chillicothe, he always considered Tukabatchee his home. Tecumseh had a lasting impact on the Piqua Shawnee, the Creek, and the Chickamauga Cherokee in their efforts to remove the settler colonists.

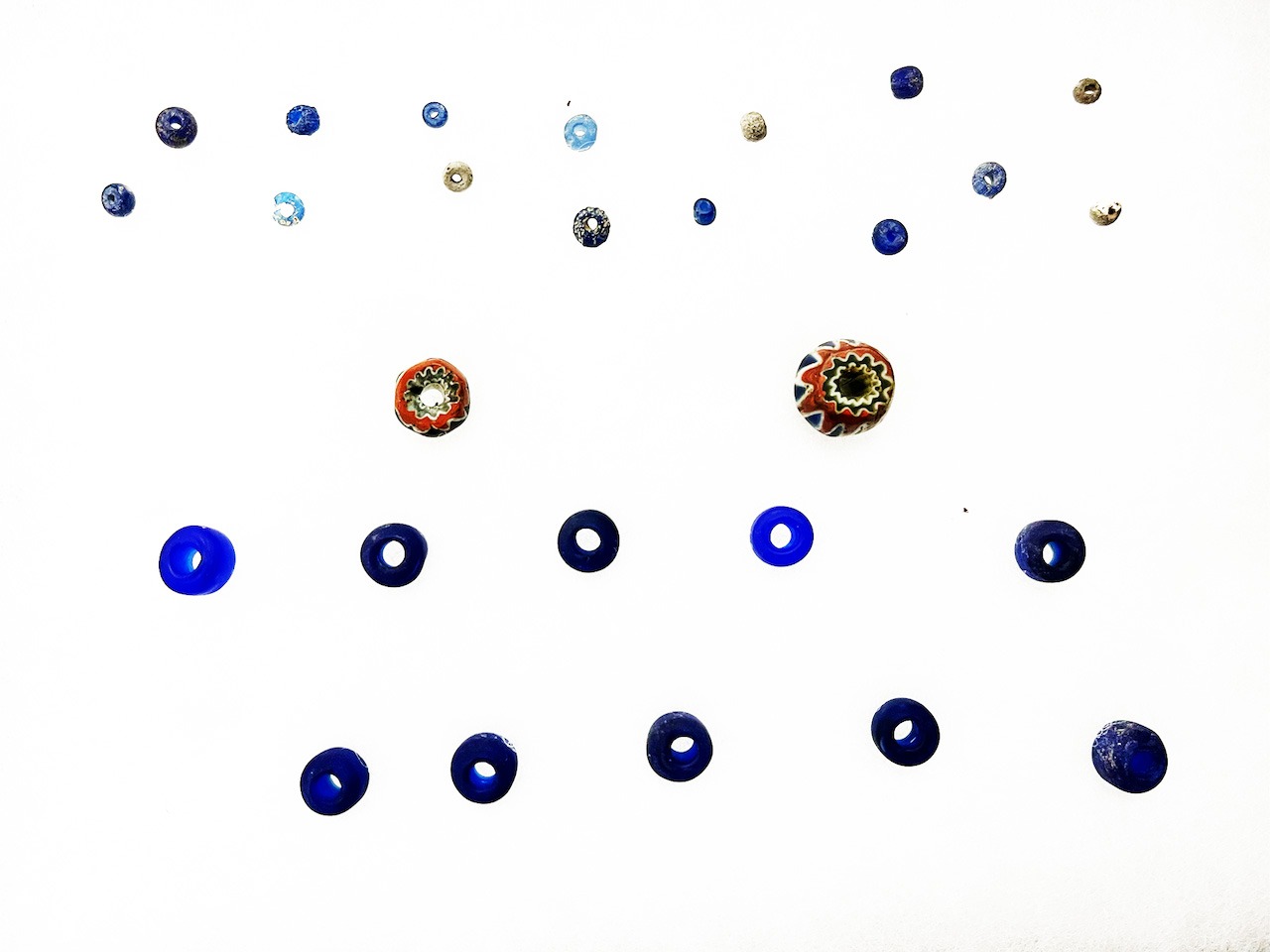

Figure 3. Piqua Shawnee Spanish colonial glass trade beads. Chevron beads ca. 1540-1640 CE. Large and small blue glass beads ca. 1620-1640.

Figure 4. Piqua Shawnee French colonial gunflints, ca. late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Figure 5. Piqua Shawnee brass tomahawk pipes obtained from French colonial traders ca. 1760-1830. Brass tomahawk pipes, also known as pipe axes, were used as weapons of war and as pipes to smoke with friends and used in ceremonies.

Strategy for Wartime

The Piqua Shawnee joined the Creek Confederacy, which also included the Coushatta, Hitchiti, Natchez, and Yuchi. The primary purpose of the confederacy was to expel settler colonists and their allies from their homeland. They refused to acknowledge the 1785 Treaty of Hopewell, which surrendered all the land south of the Cumberland River. Instead, they vowed to destroy the colonial settlements in this region. Piqua Shawnee warriors joined Tsiyu Gansini’s (Dragging Canoe) Chickamauga Cherokee in the Nickajack towns on the south side of the Tennessee River in northern Alabama.

Figure 6. Historic Piqua Shawnee towns and villages.

Throughout the American Revolution, the Piqua Shawnee lived in the town of Sawanogi and among the Creek in some 50 towns along the Alabama, Chattahoochee, Coosa, Flint, and Tallapoosa rivers. England embraced the fact that the Piqua Shawnee, Cherokee, and Creek were trying to rid Alabama of settler colonists. The British government successfully secured their efforts in fighting against the continental army and militias.

Figure 7. Homeland of the Piqua Shawnee.

Following General Andrew Jackson’s 1818 invasion of the region, the United States repeatedly tried to persuade the Piqua Shawnee to join the emigrating Cherokee and move west of the Mississippi River. They consistently refused to give up their Alabama homeland. In 1830, President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act, which led to the federal government forcibly removing Native Americans from their homes in Alabama to the Oklahoma Indian Territory. By 1832, the Piqua Shawnee had concealed themselves from census takers. To escape forced removal to reservation land west of the Mississippi River, they concealed themselves east of the Coosa River around Kymulga (old Shawnee town) and Kymulga Cave.

The New Order

The Piqua survived forced removal by publicly suppressing their culture and heritage, generation after generation. After almost two centuries of cultural concealment, the Piqua continue to survive in their homeland as they have since time immemorial. In 1984, the Alabama House and Senate passed the Davis-Strong Act, which created the Alabama Indian Affairs Commission (AIAC). On July 10, 2001, the AIAC recognized the Piqua Shawnee as one of nine tribes in Alabama. As a state-recognized tribe, the Piqua Shawnee have a legal status and governmental authority.

Further Reading

Adair, James. The History of the American Indians. London: Edward and Charles Dilly, 1775.

Brannon, Peter A. Handbook of the Alabama Anthropological Society. Alabama Montgomery: Anthropological Society, 1920.

Braund, Kathryn E. Holland (ed.) The History of the American Indians by James Adair. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2005.

Dowd, Gregory Evans. A Spirited Resistance: The North American Indian Struggle for Unity, 1745–1815. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993.

Morgan, Ruth, Janet Clinger, Kenneth Barnett Tankersley, Barbara S. Lehmann. Piqua Shawnee: Cultural Survival in their Homeland, Berkley: Community Works West, 2018.

Pate, James P. The Annotated Pickett’s History of Alabama and Incidentally of Georgia and Mississippi, from the Earliest Period. Montgomery: New South Books, 2018.

Sugden, John. Tecumseh: A Life. New York: Henry Holt and Company. 1997.

Swanton, John Reed. Early history of the Creek Indians and their neighbors. Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1922.

Tankersley, Kenneth Barnett. Cherokee of the Cumberland. Milford: Little Miami Press, 2022.

Warren, Stephen. The Worlds the Shawnees Made: Migration and Violence in Early America. Chappel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014.

Join our Mailing List

Sign up for news on upcoming events near you and around Alabama.